Page 16 - Masala Lite Issue 166 October 2024

P. 16

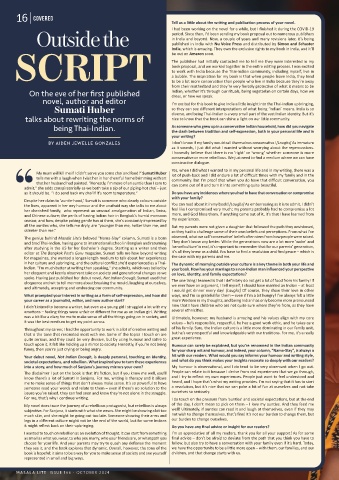

16 COVERED

Tell us a little about the writing and publication process of your novel.

I had been working on the novel for a while, but I finished it during the COVID-19

period. Since then, I’d been sending my book proposal out to numerous publishers

in India and beyond. Now, a couple of years and many revisions later, it’s being

SCRIPT be out on Amazon soon.

published in India with Nu Voice Press and distributed by Simon and Schuster

India, which is amazing. They own the exclusive rights to my book in India, and it’ll

The publisher had initially contacted me to tell me they were interested in my

book proposal, and we worked together in the entire editing process. I was excited

to work with India because the Thai-Indian community, including myself, live in

a bubble. The inspiration for my book is that when people leave India, they tend

to be a lot more conservative than people who live in India because they’re away

from their motherland and they’re very fiercely protective of what it means to be

On the eve of her first published Indian, whether it’s through our rituals, being vegetarian on certain days, how we

dress, or how we speak.

novel, author and editor I’m excited for this book to give India a little insight into the Thai-Indian upbringing,

Sumati Huber so they can see different interpretations of what being ‘Indian’ means. India is so

diverse, and being Thai-Indian is a very small part of the vast Indian identity. But it’s

talks about rewriting the norms of nice to know that the book can shine a light on our little community.

being Thai-Indian. As someone who grew up in a conservative Indian household, how did you navigate

the clash between tradition and self-expression, both in your personal life and in

your writing?

BY AIDEN JEWELLE GONZALES I don’t know if my family would call themselves conservative! [Laughs] As immature

as it sounds, I just did what I wanted without worrying about the repercussions.

I honestly believe that there is no ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ whether someone is more

conservative or more rebellious. We just need to find a medium where we can have

constructive dialogue.

Yes, when I did what I wanted to in my personal life and in my writing, there was a

My mum will kill me if I didn’t serve you some chai and food!” Sumati Huber lot of push-back and I did endure a lot of difficult times with my family and in the

tells me with a laugh when I visit her in her cheerful home brimming with art community. But I’m proof that when you do have that difficult conversation, you

that her husband had painted. “Honestly, I’m more of an auntie than I care to can come out of it and turn it into something quite beautiful.

admit,” she adds conspiratorially as we both take a sip of our piping-hot chai – just

as it should be. “I do send back my chai if it’s room temperature.” Do you have any incidences where you had to have that conversation or compromise

with your family?

Despite her claim to ‘auntie-hood,’ Sumati is someone who clearly colours outside

the lines, apparent in her wry humour and the unafraid way she talks to me about You can read about it in my book! [Laughs] As embarrassing as it is to admit, I didn’t

her cherished family, who represent an unusual amalgamation of Indian, Swiss, feel like I compromised very much; my parents probably had to compromise a lot

and Chinese culture; the perils of having Indian hair in Bangkok’s humid monsoon more, and God bless them. If anything came out of it, it’s that I have learned from

season; and how, despite poking gentle fun at them, she’s constantly impressed by my experiences.

all the aunties who, she tells me dryly, are “younger than me, hotter than me, and But my parents were not given a daughter that followed the path they envisioned,

skinnier than me.” so they had to challenge some of their own beliefs and perceptions. From what I’ve

The genius behind Masala Lite’s beloved “Nama-Slay” column, Sumati is a born observed, what we call ‘conservative’ beliefs often stem from how people were raised.

and bred Thai-Indian, having gone to international school in Bangkok and returning They don’t know any better. While the generations now are a lot more ‘woke’ and

after studying in the US for her Bachelor’s degree. Starting as a writer and then ‘cancel culture’ is real, it’s important to remember that for our parents’ generation,

editor at The Bangkok Post’s Guru magazine, Sumati tells me how beyond writing it’s all they knew as a child. You have to find a resolution and find peace – which is

for magazines, she wanted a longer-length medium to talk about her experiences the case with my parents and me.

in her culture and upbringing, and the cultural conflict she’d experienced as a Thai- The dynamic of marrying outside your culture is a key theme in both your life and

Indian. “I’m much better at writing than speaking,” she admits, which was belied by your book. How has your marriage to a non-Indian man influenced your perspective

her eloquent and keenly observant take on society and generational changes as we on love, identity, and family expectations?

spoke. Having just published her debut novel, Not Indian Enough, Sumati used that

eloquence and wit to tell me more about breaking the mould, laughing at ourselves, The one thing I learned is that I definitely do not get a lot of food from his family! If

and ultimately, accepting and embracing our community. we ever have an argument, I tell myself, I should have married an Indian – at least

I would get dinner every day! [Laughs] Of course, they show their love in other

What prompted your interest in writing as a form of self-expression, and how did ways, and I’m so grateful for them – even if I’m a bit hungry! I’ve always felt a litt le

your career as a journalist, editor, and now author start? more Western in my thoughts, and being Indian has only become more pronounced

I didn’t intend to become a writer, but even as a young girl I struggled a lot with my now that I have children who are not quite sure where they’re from, as they have

emotions – feeling things were unfair or different for me as an Indian girl. Writing several ethnicities.

was a bit like a diary for me to make sense of all the things going on in society, and Ultimately, however, my husband is amazing and his values align with my core

it was the best medium to get my point across. values – he’s responsible, respectful, he has a good work ethic, and he takes care

Throughout my career, I had the opportunity to work in a lot of creative writing and of his family. Sure, the Indian culture is a little more dominating in our family unit,

that is the tone that resonated most with me. Some of the topics I touch on are but he’s very respectful and knowledgeable with our traditions. For me, it’s a really

quite serious, and they could be very divisive, but by using humour and satire to great experience.

touch upon it, it felt like holding up a mirror to society. Honestly, if you’re not being Humour can rarely be explained, but you’re renowned in the Indian community

funny, then you’re just crying or being angry. for your sharp wit and humour, and indeed, your column, “Nama-Slay”, is always a

Your debut novel, Not Indian Enough, is deeply personal, touching on identity, hit with our readers. What would you say informs your humour and writing style,

societal expectations, and rebellion. What inspired you to turn these experiences and what do you think makes your insights resonate so deeply with our readers?

into a story, and how much of Sanjana’s journey mirrors your own? My humour is observational, and I do tend to be very observant when I go out.

The disclaimer I put on the book is that it’s fiction, but if you know me well, you’ll People can relate to it because I derive from real experiences that we go through,

know there’s a lot of Sumati in Sanjana. For me, writing is therapy and it allows and I try to reflect my own experiences. People just want to feel understood and

me to make sense of things that don’t always make sense. It’s so powerful to have heard, and I hope that’s what my writing provides. I’m not saying that it has to start

someone read your words and relate to them – even if there’s no solution to the a revolution, but it’s nice that we can poke a bit of fun at ourselves and not take

issues you’ve raised, they can feel seen and know they’re not alone in the struggle. ourselves so seriously.

For me, that’s why I continue writing. I do touch on the pressure from ‘aunties’ and societal expectations, but at the end

My novel does trace the journey of a rebellious protagonist, but rebellion is always of the day, I don’t mean to pick on them – I love my aunties. And they feed me

subjective. For Sanjana, it starts with what she wears. She might be showing a bit too well! Ultimately, if aunties can read it and laugh at themselves, even if they may

much skin, and she might be going out too late. Someone showing their arms and not wish to change themselves, that’s fine! It’s not our burden to change them, but

legs in a different culture might not be the end of the world, but for some Indians our burden to change ourselves.

it might reflect back on their upbringing. Do you have any final advice or insight for our readers?

I wanted to touch on rebellion as an evolution of thought. It can start from something I’m so appreciati ve of all my readers, thank you for all your support! As for some

as small as what you wear, to who you marry, who your friends are, or what path you fi nal advice – don’t be afraid to deviate from the path that you think you have to

choose for your life. And your parents may try to quash any defiance the moment follow, but also try to have a conversati on with your family even if it’s hard. Today,

they see it, and the book explores that dynamic. Overall, however, the tone of the we have the opportunity to be a litt le more open – with them, our families, and our

book is hopeful; it aims to be a way for you to make sense of society and see yourself children, and that change starts with us.

represented in small and big ways.

MASAL A LITE ISSUE 166 - OCTOBER 2024